the ritual of the algorithm

what do we think is happening online?

I’ve been reading a lot about rituals lately.

It’s fascinating how the most important aspects of society all depend on some kind of ritual: graduations, inaugurations, baptisms, marriages—the list goes on. As humans, we depend on these rituals to contextualize our lives, and yet we rarely think about how similar these actions are to each other.

The ethnographer Arnold van Gennep identifies three stages to each ritual:1

Separation: removal from ordinary or social life.

Margin or limen: a threshold between past and present modes of existence.

Re-aggregation: the return to mundane life, in an altered or higher status.

“Separation” is often instigated by a particular marker: Pomp and Circumstance starts playing, the clock strikes noon on inauguration day, or the bride walks down the aisle to Mendelssohn’s Wedding March. This marker is important, because it segments off this piece of reality as special, telling us that the ritual has begun.

Then a transition happens: a limbo between states of reality. An academic procession occurs, wedding vows are exchanged, an oath of office is taken. Finally, something marks the end of the ritual. The degree is conferred, the couple is pronounced man and wife.

But what was the point? You can just sign your papers at City Hall or get your diploma in the mail. Clearly, the ritual isn’t necessary—but in another sense, it is, because it’s a social signal of the transition. It allows us, and others, to process what’s happening. In the words of the anthropologist Victor Turner,2

“To look at itself a society must cut out a piece of itself for inspection. To do this it must set up a frame within which images and symbols of what has been sectioned off can be scrutinized… what is inside the frame is what is often called the "sacred," what is outside, the "profane," "secular," or "mundane." To frame is to enclose in a border.”

Critically, this means that anything can function as a ritual, as long as we mentally frame it as a discrete event. Clubbing, for example, has frequently been analyzed through the ritual framework. We separate ourselves through the visual marker of passing the bouncer, and then enter a liminal, separate world where we can lose ourselves in the music, forgetting about our normal lives (until we eventually stumble back to coat check).3

If we stretch the lens further, any mundane act is also a ritual, due to the very fact that we can categorize it. Voting, travel, sex, and work all exist as distinguishable actions in our minds. We dress differently for the office. We check in for our flights. In short, we enclose these parts of reality in neat frames so that we can understand them better. Even though our lives are messy and continuous, these micro-rituals allow us to pretend that it’s neat and discrete, in a way that makes more sense to us.

The downside is that we create “innie” and “outie” versions of ourselves, where the person in the ritual is somehow different than the person outside. We pretend that our “work self” is separate from our “real self,” even if these exist in the same reality.

The same is true on social media. The act of opening the app is the first phase of the ritual. As I wait expectantly in the comforting glow of the TikTok loading screen, I can feel myself slipping into the “algorithmic self,” the version of myself that exists in the scrolling flow state (and enabled by the assumption that the algorithm is in fact targeted to me). While perceiving the videos themselves, I can only describe the experience as liminal: a sort of suspended time corresponding to the second phase of the ritual. Finally, exiting the app brings me back to my “real self.”

As with more ceremonious events, this “algorithmic ritual” segments off a portion of my existence. Within it, I am dissociated from reality much like being in the club, or graduating, or getting married. And just like those events, I treat it as a microcosm of reality, interpreting “sacred” signs and symbols that help me contextualize my existence.

Although we like to pretend otherwise, the memes, trends, and language of social media aren’t isolated to some online vacuum. They are part of who we are, and are used to reflect on culture as a whole. We eventually bring online attitudes to the offline in our humor, consumption patterns, and slang. Even “brainrot” speaks to us because it responds to real pressures in society.

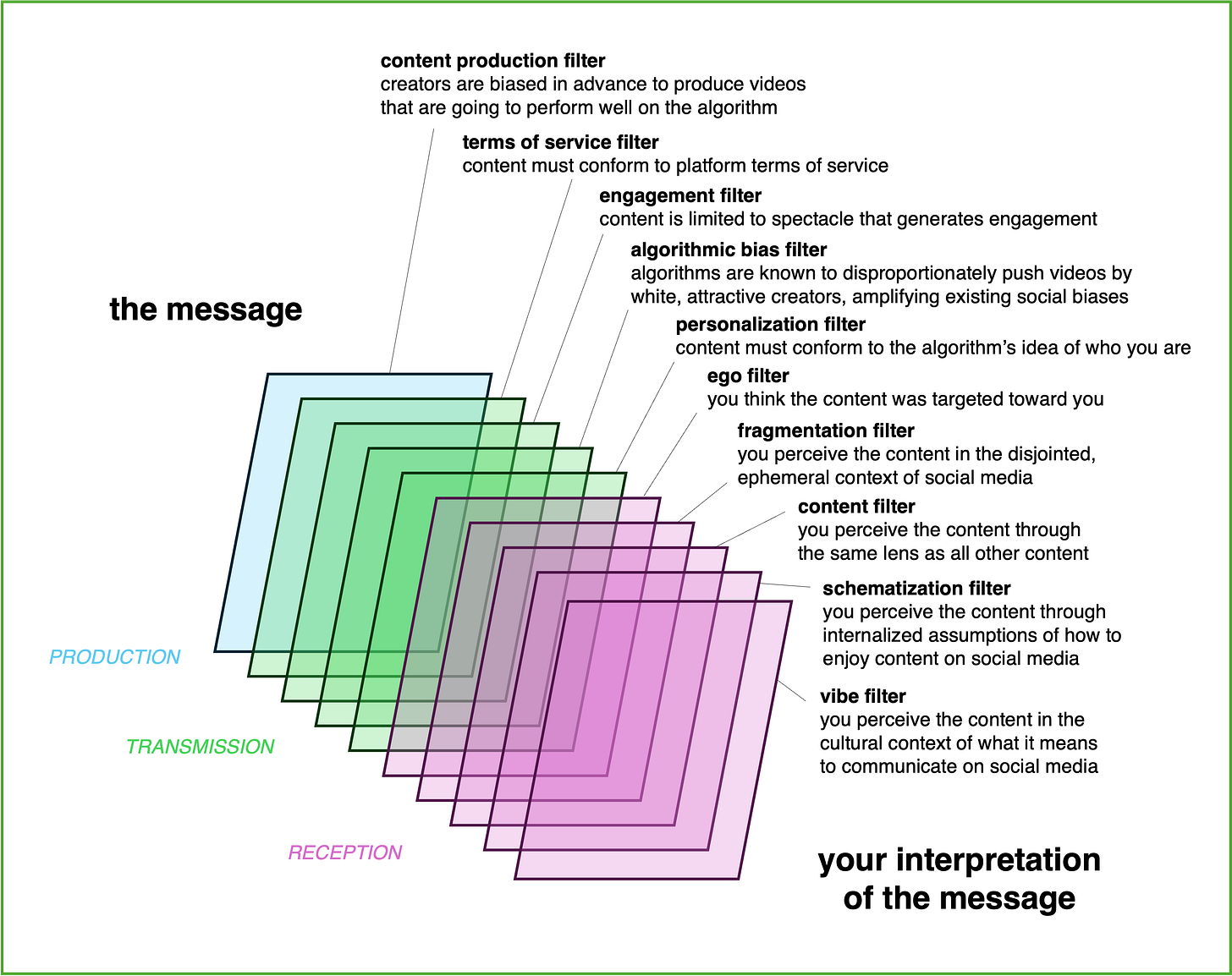

Nevertheless, the symbols and signs that I perceive within the “algorithmic ritual” are limited to a slew of content filters that distinguish the platform’s version of reality from objective reality.

Because of the “algorithmic gaze”—the act of forgetting that these filters exist—this ritual poses a problem: that we treat it as a “piece of society” for inspection, and yet it only represents one constrained representation of it.

And since the map bleeds into the territory, this means that the millions of people building their reality around the algorithmic ritual are on some level internalizing its programmed passivity. By treating the platform’s frame as real, we start to shape our actual discussions through the window of what’s allowed online. For example, the fact that the word “cisgender” is censored on X or that criticism of the tech industry is censored on Facebook means we’re having fewer online discussion of those topics, and your “algorithmic self” is thus perceiving fewer “sacred images” of those ideas to report back to your “real self.”

We can’t avoid ritualizing and narrativizing. It’s part of what makes us human. But we can build our rituals and narratives around other sources that give us a better picture of reality. That might just be our best way of fighting back.

If you liked this analysis, please consider pre-ordering my book Algospeak, on the intersections between algorithms and communication!! Pre-ordering is the best way to support authors :)

You can also register to attend my book launch in the Strand Bookstore on July 14 by following the link here. Thanks for your support!!

Van Gennep, Arnold. The Rites of Passage. University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Turner, Victor. "Frame, Flow and Reflection: Ritual and Drama as Public Liminality." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (1979): 465-499.

Goulding, Christina, and Avi Shankar. "Club culture, neotribalism and ritualised behaviour." Annals of Tourism Research 38.4 (2011): 1435-1453.

This reminds me a lot of when I was trying to understand state-dependent memory.

We can intuit it quite easily in regards to being intoxicated, but when you look really closely, you'll see that the boundaries between different "states" for state-dependent memory are considerably more numerous than we might realize.

Like walking through a doorway, or getting up from sitting/lying down after doing so for a long time. There's lots of location-based ways to make our short-term memory do a soft reset, and I feel like maybe that's an important factor in these different selves you're talking about!

So when you talk about slipping into our "algorithmic selves", I wonder what state-dependent properties of our minds are changing?

great article as always but definitely freaks me out a little bit. I don’t like the idea of people’s perception of world being altered by corporations running social media without people realizing it’s happening to them. I’m seeing more pushback against social media in general that I’m happy about, seeing people recognizing that.