I’m flying on a plane from Bangkok to Taipei, and I can’t help but think in stories.

Stories are essential to human communication—in fact, some theorists argue that communication is impossible without storytelling. By telling you that I’m flying from one city to another, I’m establishing start and end points for my story. By introducing the plane, I’m explaining how the story unfolds.

In reality, stories don’t exist outside of our cognition. The idea that time can be broken down into meaningfully discrete lengths is a human construct. I existed before I left Bangkok, and I’ll exist after I land in Taipei, but I’ve chosen to segment off this portion of my existence to make better sense of it and build a meaning-making narrative.

In the same way, I use the “plane” as a storytelling device to simplify the unthinkably complicated factors coming together to take me across the South China Sea. My plane is made of many tiny pieces, but I’m choosing to view it as a single object because it makes more sense to talk about it that way. There are countless technological and physical processes happening to keep me in the air, but it’s easier to ignore that and just say that I’m “flying.”

All humans do this because our brains are wired to make meaning out of chaos. If I didn’t tell myself the story “I’m on a plane,” my brain would be overwhelmed by how to process the sensory input of seats, aisles, overhead cabins, and clouds zipping by outside. Similarly, if I didn’t tell myself the story “I’m going from Bangkok to Taipei,” I would find myself in a different city wondering how the hell I got there.

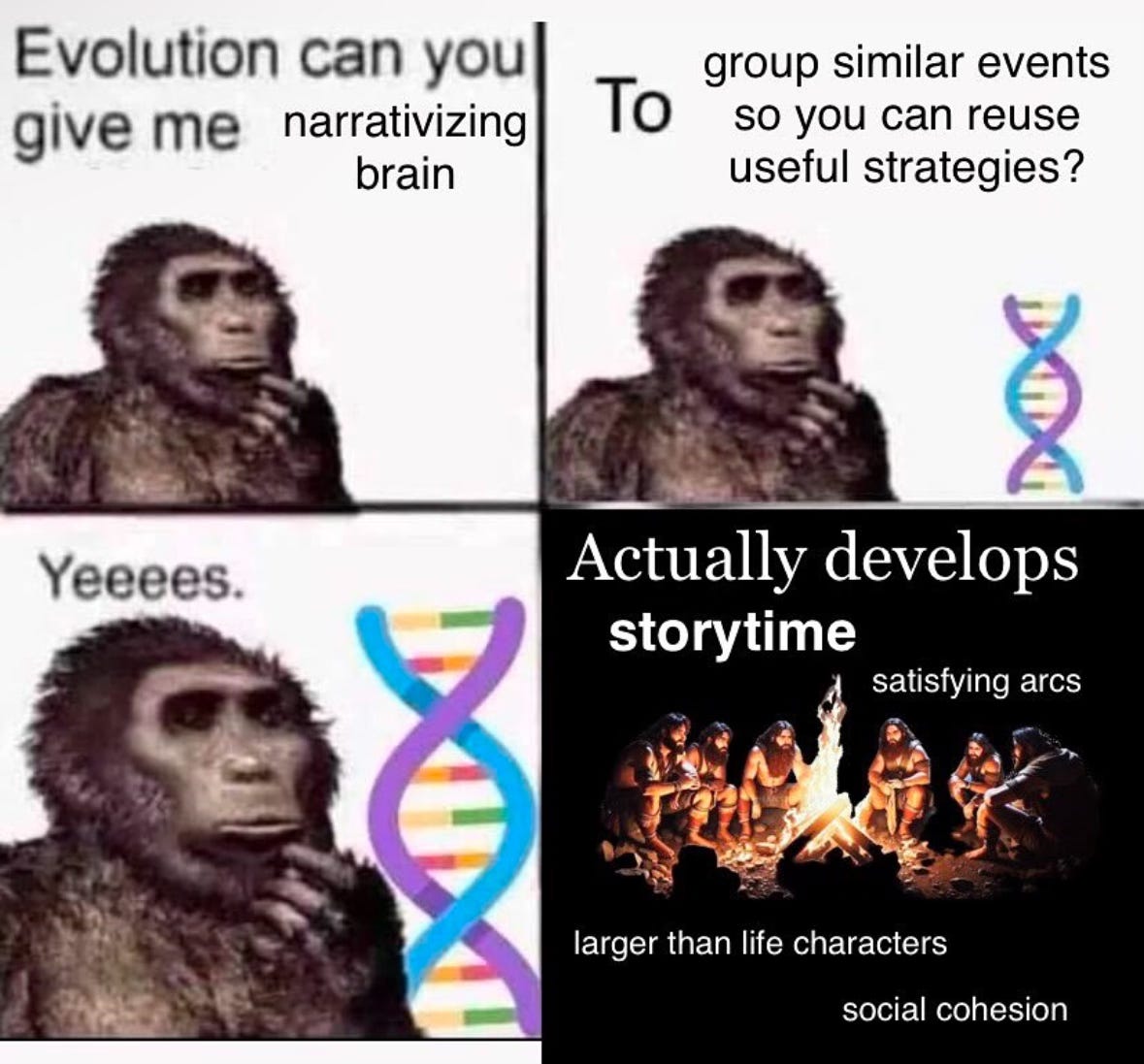

You simply need to make stories from a biological perspective. Without organizing observations into cause-and-effect lessons, how can you absorb and retain information crucial for your survival? Without categorizing interactions with other people, how can you feel empathy or bond with them? As a result, your hippocampus has evolved to arrange everything into neatly packaged logical sequences for you.

While our need to tell stories is inherent, the way we tell stories can change over time. Even beyond the ever-evolving vocabulary and grammar we use, the medium of the story affects how it’s told. Prior to written history, more stories were told through song, because it’s easier to remember things when there’s a melody involved. Likewise, once we started writing stuff down, we unlocked more nuanced ways to express and abstract ourselves. Each successive technological development has changed storytelling in some way: mass printing let us tell stories to broader audiences, while television allowed us to visually express stories.

In the past five years, the rise of short-form video content has continued to add innovations to our narrative canon. Consider the emergence of POV videos, which invite the viewer to experience stories in the first rather than third person. This new genre of storytelling has so profoundly changed our culture that the abbreviation pov has become a discourse marker indicating the beginnings of stories in everyday memes.

I really like pov because it reflects the heightened importance of the self in the social media zeitgeist. We’re regularly encouraged to do things for the plot and talk about our lives as if our lore can be divided into arcs or seasons with established canon events. Meanwhile, peripheral people and tasks are written off as NPCs and sidequests, separate from the “main character” plotlines we’ve espoused. Effectively, it seems like our storytelling is becoming more narrative-driven with the current cultural moment.

Of course, I’m packaging this analysis as a story as well. There are many reasons why we might be using certain slang, and presenting a single framework helps me make sense of something incredibly complex. But what else can I do? My plane is landing.

also here’s a new op-ed I wrote for the Washington Post that tangentially examines this phenomenon from a different angle

pov: i am reading this essay

pov: ur in the comment section