There’s something about TikTok that just works better on your phone.

You can easily access the platform through its website or your smart TV, but something is immediately diluted in the experience. You lose that passive, amniotic closeness of being curled up under your covers with your phone glowing in front of your face, able to summon new videos with each swipe of your thumb.

If anything, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that people would rather watch TV on TikTok than TikTok on TV. The app is simply more intimate, more engaging, more addicting than any other medium.

The Wired writer Leo Kim argues that this goes back to the fact that we’re all cyborgs. In the same way that our bodies are part of who we are, so too have our phones become a functional extension of our minds. We feel naked when we go anywhere without them, and to use them is to project our consciousness into the delicate haptic experience of thumb on screen. As such, we feel much closer to our phones than we do our computers or TVs, and enter a kind of “flow state” of media consumption when interacting with them. The rest of the world blurs away as we enter a tender, individualized connection with this unique part of ourselves.

TikTok was the first to truly tap into this sensation by making the video dominate your entire phone screen, and therefore your entire attention. The algorithm, coupled with the simple logic of swiping up, automated the act of choosing your next video; the promise of personalization further established this notion of your feed being an extension of yourself. This engendered an unprecedented feeling of numb passivity.

In his 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the philosopher Walter Benjamin voices his concerns on how the rise of photography and cinema affected our aesthetic experience of media. Film, for example, penetrates deeper into reality than the theater stage, where it’s obvious that the story is unfolding in a manufactured medium. This can cloud the viewer’s critical lens: whenever they think they’re identifying with an actor, they’re really identifying with the gaze of a camera.

Today, social media algorithms represent another abstraction. When you watch a movie, you still frequently do so with a critical lens, thinking about the film as you perceive it. However, the line between phone and consciousness is far blurrier. One can mindlessly scroll for hours, perceiving but not analyzing.

And yet, the more we immerse ourselves in short-form video, the easier it is to forget how the medium affects the message. To identify with an influencer is to not only identify with the camera perspective, but also with the algorithm that brought you that video.

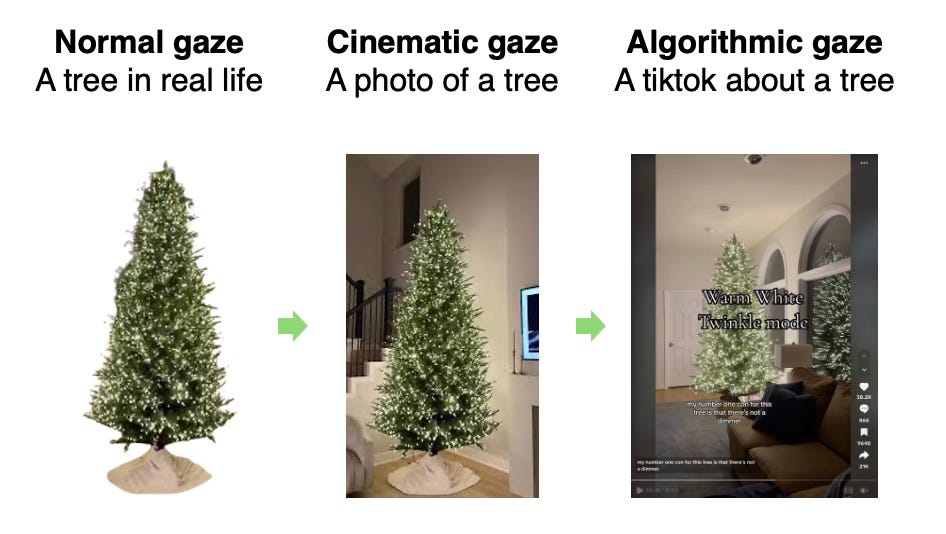

I call this the “algorithmic gaze.” Just as the camera controls what we see through the “cinematic gaze,” the algorithm also controls what type of content is even brought to us in the first place (an idea I heavily explore in my upcoming book Algospeak).

Consider the classic example of cinematic gaze: the depiction of women. Historically, art and cinema have consistently portrayed women as the objects of male desire, perpetuating a patriarchal ethos through their storytelling. Those same visual narratives now exist in any viral video with a woman in it. Social media algorithms disproportionately push videos of attractive, particularly sexualized, women to male audiences because it’s shown to drive engagement on their respective platforms.1 As a result, many female creators feel forced to performatively film for the male gaze for their videos to even be seen. Even those that don’t wish to conform inherently do: TikTok has previously been proven to suppress videos by “ugly” creators, meaning that most posts on the For You Page inherently passed through algorithmic filters of “attractiveness.”

Most of us don’t consider this when we’re in our “flow state” of scrolling. We’re too distracted by dopamine delivery, too captivated by the psychosomatic hypnosis of holding phone in hand. We consume mechanical reproduction of mechanical reproduction, eventually losing touch of what Benjamin labels “aura”—the sublime experience of reality that reminds us to think critically.

See my follow-up post here.

Cotter, Kelley. "Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram." New Media & Society 21.4 (2019): 895-913.

this is something i’ve been silently bubbling about recently. i tend to dislike podcasts because they ought be engaged with critically (unless it’s some gossip/drama program, i guess) but people listen to them passively. too much of the information we absorb is taken as is without much thought.

hell, even taking pictures has become focused on where it’s getting posted as opposed to capturing a moment or scene. like you pointed out, it could be argued that the photograph itself impels the viewer to associate with the camera, the scene set and lighting utilized, to alienate one step from the base material. we’re moving further into this false reality, which would be fine if it was honest in its fictitious presentation, but it attempts to pass as reality itself, and coupling with helpless addiction, subsumes reality itself for many.

It's a constant fight to avoid interaction with glossy, shiny TikTok. But it can be done.

My FYP is full of intellectual dopamine hits. TikTok basically replaced my desire to play Wikipedia roulette, or read encyclopedias for fun. However, rather than have faceless editors, it's nice to experience the passions and hyper fixations of other people, as they emote passion for their interests.