One of the most frustrating things about studying language is knowing that it will never perfectly capture reality.

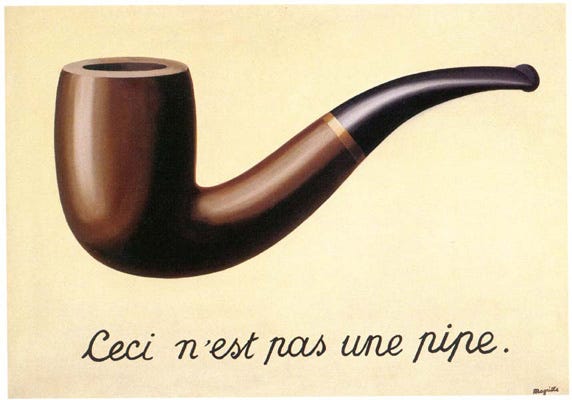

There’s a thing, and then there are our words for the thing, but these are never the same. Sure, a word can evoke a mental image of the thing, the same way a picture of a pipe can evoke the concept of a pipe, but it’s never the thing itself.

This relation is often described with the sentence “the map is not the territory,” drawing on the Borges story about an empire that produces a map as large as the empire itself. Upon completion, they realize that the map is useless—pointing to the fact that no representation can ever capture reality unless it subsumes reality itself.

Social media is much like language: it’s a map purporting to represent the territory, but can never truly do so. Whatever you see online is inherently limited by what is available on the platform, which means it can never coincide point-for-point with what is available in reality. Let’s say you have some weird esoteric interest like underwater basket-weaving, but the algorithm only has regular basket-weaving videos. Even though your real self wants the former, your algorithmic self is only ever going to get the latter.

Similarly, AI models will align everything with a limited generative vocabulary, working with broad metadata that can’t actually label the world as it exists. This means that LLMs are first limited by the usual constraints of our language, and then by what they can extrapolate from that language.

However, as I’ve previously written, social media platforms want us to think that their map is the territory, because that helps their business model. The more we confuse their “content” with reality, the more we identify with it. Over time, you might really find yourself pursuing regular basket-weaving instead of underwater basket-weaving, simply because that’s what’s available to connect with—but that makes you easier to target as a consumer, since you’re now aligning your identity with the kind of broad metadata the algorithm is able to work with.

Once you identify with the algorithmic version of reality, the manufactured values of the platform become synonymous with your actual values. Content is presented as if it’s “good”—after all, it’s targeted for you, and has lots of “likes” from other people—but these metrics are made up. They reflect the platform priority of engagement optimization, rather than actually being intrinsically “good” or targeted to you.

Nevertheless, you forget that, because you’re distracted by what the philosopher Guy Debord calls spectacle: a separate pseudo-world that can only be looked at, and yet masquerades as society itself. To Debord, “the spectacle presents itself as something enormously positive…it says nothing more than that which appears is good, that which is good appears.” In social media terms, that’s an Instagram picture of a pipe, telling you it’s better than a real pipe because it has lots of likes, while the actual one doesn’t.

The end result is that some people will produce more spectacle than reality. In my recent post on racist Instagram Reels, for example, I found that the creators of these reels aren’t making them for any political agenda, but just because they generate engagement. In effect, they’re making “content” for the sake of “content,” not for any real message. I’m reminded of the following sentence from Debord:

“The basically tautological character of the spectacle flows from the simple fact that its means are simultaneously its ends.”

On Instagram and TikTok, the “means” for communicating are “going viral.” Many creators treat these means as an end—they prioritize virality over communication, confusing the map with the territory.

To be clear, all algorithmic content has to play into spectacle. I often start my videos with sensational hooks, speaking in an exaggerated accent, because I know that performs better. I still have real messages to communicate, but I’m also helping the platform generate revenue.

That’s because, even if the map isn’t the territory, it isn’t separate either. A picture of a pipe is still a tangible thing that exists in real life. As such, the spectacle will unfold within the real.

I think this is an important feature of modern memes. Apart from the racist slop, which seems like pure spectacle, most “AI brainrot” derives its absurdity from the coexistence of the real and the hyperreal—acknowledging its own role in the algorithmic and generative environments, and thus serving as a subtle act of resistance.

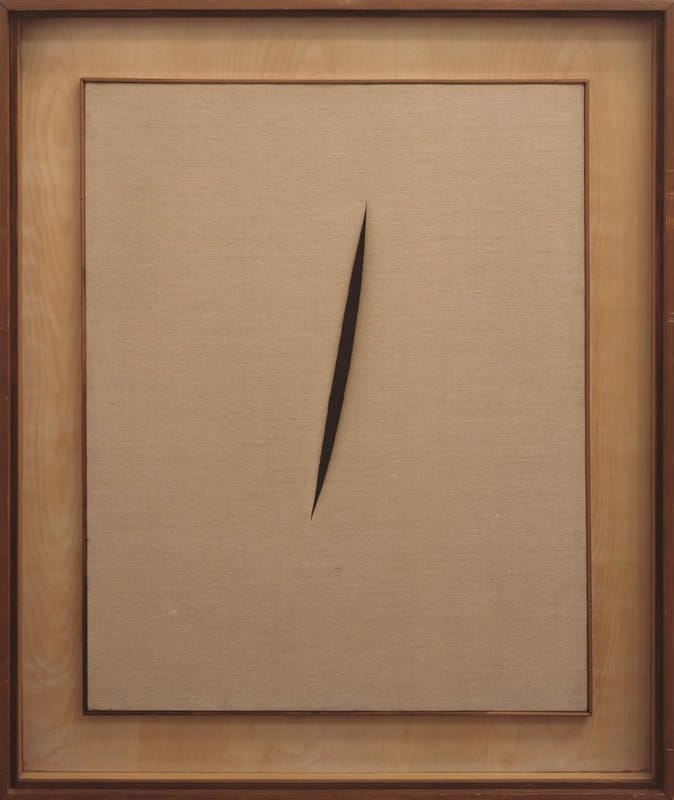

I’m reminded of Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Concept: Expectation, which is an unassuming brown canvas hanging on the fourth floor of the Museum of Modern Art, distinguished by a single slash running down the center. Although it doesn’t seem like much, this slash shatters the illusion of a “painting” and leaves you contemplating a “real cut” in the canvas.

Fontana’s work is the next evolution of Magritte’s pipe. The representation is still there, but bleeding into actual existence—and I would say this is more characteristic of our experience on social media.

We might prefer to compartmentalize our “algorithmic selves” from our “real selves” like we’re characters on Severance, but the truth is that they’re both constantly influencing each other. You get basket-weaving videos because you have a latent urge to pursue underwater basket-weaving, and then you ultimately take regular basket-weaving classes because you identified with the spectacular presentation of reality.

Our memes and language are similarly always evolving online and offline, with both mediums constantly influencing each other. The territory affects the map we draw, and then that map affects how we interact with the territory. This is inevitable—it’s just useful to remember which is which.

Much of this Substack post was inspired by a recent live conversation I had with meme researcher Aidan Walker. View the entire conversation below:

I’m also excited to announce that I’m launching my book in the Strand in NYC!! The event is this July 14 at 7 pm—get your tickets here.

so that's why all the baskets in the stores are dry and I've only been able to weave dry basket, darn

i love what you write!!!

my further thoughts:

thinking beyond basket weaving and extreme content,

why do we think it's a good idea to communicate with friends and family and local businesses and local events and everything else in real life through these companies and services? do we really need cellphones and the internet and freaking instagram to do basic human actions and interactions, like doing groceries, getting a cab, or hitting up a friend?

answer:

it's because it generates profit and turns these interactions into profitable labor for these companies. we are all just working for free! that's all that is! we are THAT dumb, we fell for THAT.

( it's NOT because it's """practical""". it's practical for these companies' owners (the worlds richest men and participants of the Trump administration). working for free is what you're doing when you upload a picture of your cat on your instagram stories. )