notes on slop

“Slop” is subjectively defined, and yet shares certain universal features: it is always seen as negative, and connotes mass distribution to an ignorant group of consumers.1

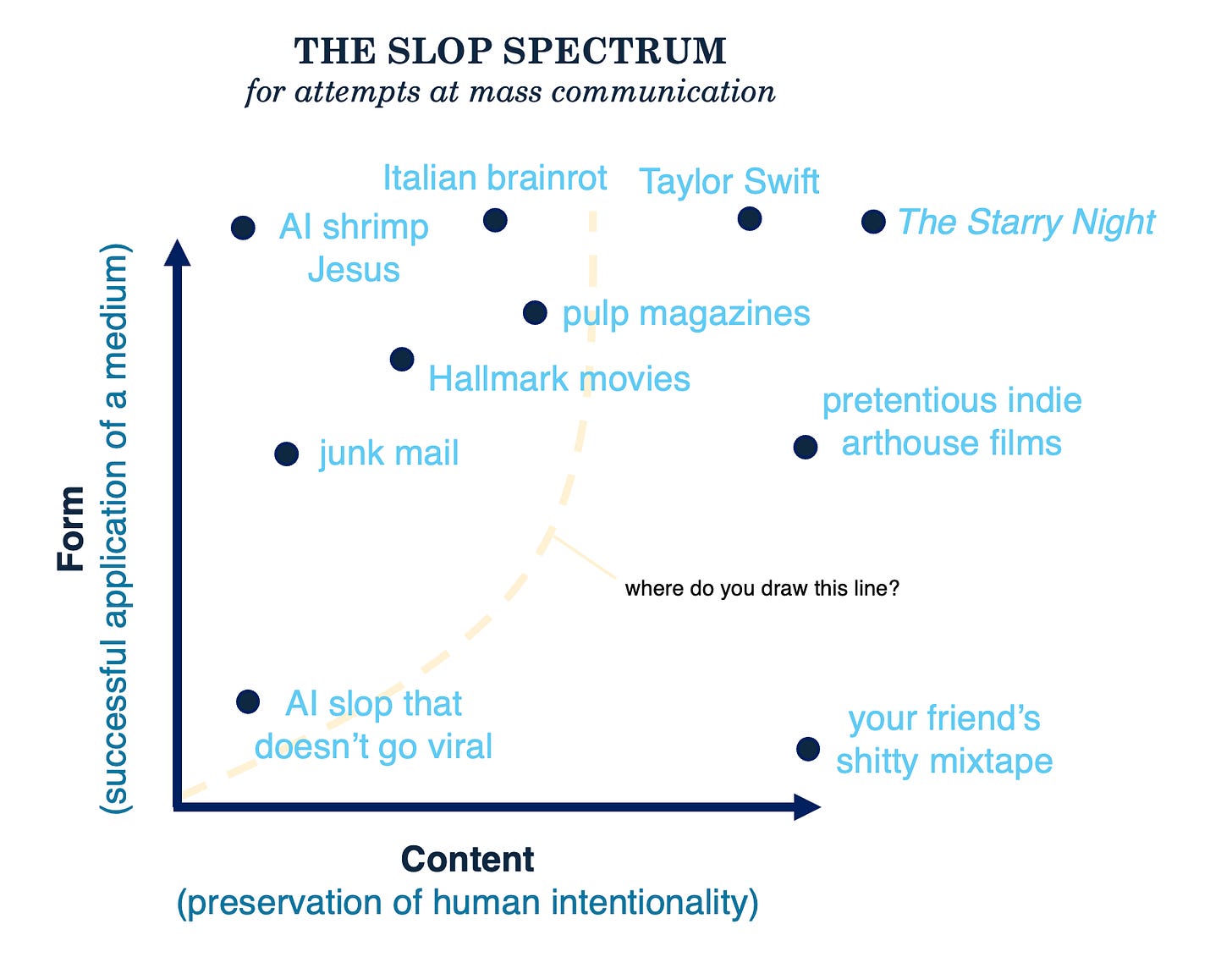

Slop is form without content. A pig’s fodder is simply meant to be food, not a type of food that does something. Instagram slop, likewise, is simply meant to go viral. It is molded in the image of the medium, recreating an idealized “successful message” rather than being a message itself.

As such, slop is intended to optimize for mass consumption. The earliest AI-generated images we consider “slop” were engineered for Facebook virality: shrimp Jesus, cat videos, and pictures of disabled veterans were deliberately designed to generate engagement and reach a broad audience.2 Whether slop actually succeeds is irrelevant: the intent is for it to be seen and heard, at the expense of meaningful communication.

Nor does slop have to be mass produced—rather, it’s something that could be mass produced (and often is). Since it has no intrinsic, unique property of its own, it is interchangeable and scalable with other slop.

Each communicative medium has its own type of slop. Hallmark movies are slop for feel-good holiday entertainment; junk mail is slop for postal advertising. “AI slop” is actually “algorithmic slop” that happens to be AI generated. The algorithm, rather than a generative model, is the communicative medium, and we already had algorithmic slop through creators like MrBeast or Jubilee Media. We perceive “AI slop” as particularly salient because of our cultural concerns about AI removing human intentionality, and because it renders mass production more accessible than before.

There is an inherent tension between using a medium for its form and for its content. A message rendered purely for form has no meaning, while a message rendered purely for content will not go viral. A “medium” poses a material constraint to our expressive intent. We typically overcome this process through creativity—figuring out how to use the form to express actual content—but the tension can never fully be resolved. Something is always lost, putting all expression on a slop spectrum. This engenders the subjectivity behind any attempt to define slop: we value what we think others put value into.

The more we sacrifice form for content, the more friction we experience. Even the word “slop” feels frictionless, like something in flow. It feels good to look at media that is good at typifying that particular medium (“high form”); it does not feel good when there is a disconnect between the message and the medium (“low form”).

This presents a pervasive issue in mass media: we consciously prefer content, but subconsciously prefer form—and our subconscious has priority. We interact with media in a flow state, naturally responding to affordances as they arise. This ease of action precedes active reflection, when we can evaluate the intellectual content of a message. If those values align, we call it “art.” If the content outweighs the form, it is “dense,” “overbearing,” “poorly executed,” or “uninteresting.” If the form outweighs the content, it is “slop.”

“Art” feels good until you’re made aware that it’s “slop.”3 The implicitly pejorative connotation of “slop” mirrors this frustration. We are upset at ourselves for enjoying meaningless drivel; we are upset at artists for producing it.

A work successfully “optimizing for mass consumption” will always provoke human response. AI shrimp Jesus and The Starry Night both emotionally resonated with millions of people. And yet Van Gogh would not go viral on TikTok, while shrimp Jesus would not be displayed in the Museum of Modern Art. This is because the world of high art retains a level of content discernment that is lost online.

The less aligned a medium is with our conscious desire for “content,” the more slop there will be, and the higher dissonance we will feel upon reflection. While the medium of “the museum” is aligned with human expression (“high in content”), the medium of “the algorithm” is aligned with generating engagement—a flattened metric of attention (which can be either “high in content” or “low in content”).

Almost all mass media outlets eventually experience slop capture, where they paradoxically need to fill space instead of communicate. Slop becomes necessary for them to function. Newspapers need to print more “new” things for their readers, so they write filler pieces; TV channels need to provide more programming, so they run crappy daytime talk shows. The outlets are forced to produce slop, providing mere form out of a lack of real content.

When a misaligned medium experiences slop capture, slop production accelerates even further. TV channels and newspapers still have some amount of editorial discretion and social prestige. Social media platforms have far fewer pretenses, and yet their business model demands them to fill far more space.4 Over time, they have created more and more structural incentives for people to produce slop, like financial incentives and the promise of virality.

Slop trains audiences to expect more slop. Newspaper readers now constantly anticipate more news, and would be disappointed if all the low-content columns were cut from their Sunday paper. A child growing up on Hallmark movies comes to associate those movies with “feel-good holiday entertainment,” and ends up wanting more of those movies. The ideal “form” of the medium evolves away from purely expressing “content,” and toward a simulation of itself. Slop capture becomes a feedback loop, unless we actually put work into discerning things ourselves.

If you enjoyed this essay, you should get my book Algospeak!! Link here.

This is reflected in the original application of the word to media: the term “goyslop” was used on 4chan to describe low-quality entertainment created by Jews to placate the masses. Although the meaning has largely evolved beyond the anti-Semitic sense, the implication remains that “slop” targets an unsuspecting majority.

All the slop creators I interviewed responded that they are making their content for banal reasons like “getting views and followers.” New York Magazine also found that slop creators will generate content with prompts like “write me 10 prompt picture of jesus which willing bring high engagement on facebook.”

See this study in Nature, showing that participants consistently rate AI-generated poetry more favorably, until they realize it’s AI.

Aidan Walker brilliantly breaks down the financial incentives behind this in his outline of slop capitalism here.

I’ve been reading a lot about communication as ritual vs communication for the purpose of sharing ideas, and particularly the notion that people who don’t enjoy small talk don’t place a high value on conversation-as-ritual, at least as compared with conversation-as-idea-exchange. It seems to me like there’s a parallel with high content/low form (idea exchange) vs low content/high form (small talk/ritual communication, slop), except maybe that ritual communication has a positive connotation for some of the participants and a pro-social purpose (connecting humans in community). Does that track?

this is making me think of disruptive innovation which is like a social innovation concept where a firm releases cheaper and simpler products (seen as worse, could be slop) that can be used by a larger number of people more conveniently. like developing minute clinics, which can quickly expand less specialized healthcare into communities vs hospitals which are more advanced but also expensive and harder to establish. similarly everyone can access and understand brainrot, can everyone access and understand fine art? maybe they can but it's a good question. theoretically, disruptive innovation can increase investment/create markets in new industries so maybe we see slop increase in prominence in the future. or slop becomes too advanced and requires too much subtext to understand and create and it loses its disruptive nature.