I interviewed the racist Instagram slop creators

on spectacle, simulation, and content hustle culture

Finally, someone else is talking about it.

Three days after I published my substack post about the influx of problematic AI-generated videos on Instagram Reels, 404 Media also came out with an article about the situation. And, as they point out, these videos contain “the most fucked up things you can imagine.”

LeBron James and Diddy raping Steph Curry in prison. George Floyd opening a fast food restaurant called “Fent-Donalds.” A swarm of shirtless Black men storming an NBA arena where they dine on fried chicken. Dora the Explorer riding a wave of feces through a Walmart and then acting out a vore fantasy.

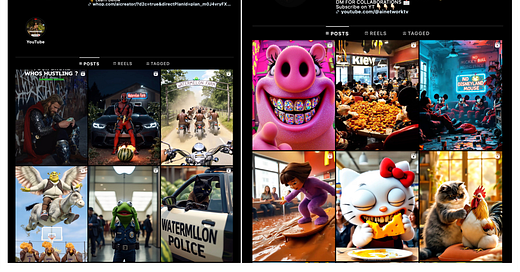

All of these videos have millions of views, collectively forming what I can only describe as a new online meme genre. Much like traditional “brainrot,” or the AI brainrot trend in Italy right now, the humor revolves around repetition of trending content. LeBron, George Floyd, and Dora join other stock characters like Shrek and Lionel Messi to form a reoccurring ensemble of viral personalities. Each video features one of a dozen set locations, including McDonald’s, IKEA, and Walmart. Even the storylines usually unfold through a predictable format: a mob running towards a commercial destination, gorging on food, and often defecating.

Notably, the most extreme videos all come from the same twenty accounts, which all seem to be familiar with each other’s work. These accounts are collectively responsible for an unprecedented shift in the Instagram memescape, and yet we know very little about them—so I reached out to interview them all. For whatever reason, five responded.

I was fascinated with who these AI creators were, why they were making this particular content, and what their underlying ideas were. I tried to gently prod at these questions, to varying degrees of success.

The most talkative account was @krazy.ai, the creator of the fried chicken video and a 24-year-old self-described “hustler” from Lithuania. After getting his start generating “history POV” videos under another account, krazy realized he could see faster growth with this “new wave of AI memes.” He justifies his controversial content choices by pointing out that they drive more engagement. “You have to stand out with your topic if you want to be first and see results,” he says. When pushed on whether he was spreading negative stereotypes, he shrugged it off. “If you don’t make mistakes, you don’t grow,” he tells me.

Krazy’s growth mindset is part of a greater AI hustle culture gripping all of these accounts: every single one of my interviewees mentioned virality and growth as key motivators behind their work. The extreme nature of their content is merely a byproduct. In the words of the Dora vore creator, @ainetworktv:

When a video reaches a certain level of grossness or weirdness that I find disturbing, I know it might go viral—so I export it and post it.

ainetworktv specifically mentions that “using recognizable pop culture characters helps catch attention,” but especially in weird or chaotic situations. 404 Media also points out that some characters and scripts are easier to generate than others; between these two explanations, it makes sense why the AI memes revolve around this particular commedia dell’arte.

I’m especially interested in the emphasis on attention and growth over all else, because it shows how the most viral creators on Instagram right now are making content for the sake of “content” and not to communicate any actual ideas. Nor are they trying to: ainetworktv openly admits to me that “there’s no deep message behind what I do.” Essentially, these accounts are racing to the bottom of what will keep our attention, filling our feeds with meaningless spectacle.

If you’ve been following my recent work, much of it examines how social media creates filters between the production and interpretation of a message, which change how we ultimately perceive certain ideas. But what happens when there’s no message in the first place? Instead of a corrupted interpretation, we’re left with no interpretation—turning us into more passive consumers along the way.

I want to make an important distinction here that I do not think all AI is inherently bad. There’s been a lot of discourse recently about how generative tools are bringing about a “semantic apocalypse” where our images and texts are going to be devoid of human meaning.

This is only true of the AI tools being used to generate “spectacle”—entertainment made purely for the sake of engagement. In many other situations, humans are using LLMs to act on their genuine ideas and creative visions, which I think is really cool. The history of language is the history of how humans use tools to communicate, and this is a new step in that history.

However, because social media platforms prioritize engagement over communication, much of the AI we see in the online setting really does lack meaning. In fact, it’s precisely that lack of meaning which gave us this current surge of disturbing memes, since they’re purely being manufactured to capture your attention. That’s where I start to get concerned.

In his 1981 treatise Simulacra and Simulation, the philosopher Jean Baudrillard warns of “hyperreality”: the inability to distinguish simulation from reality. In his vision, the hyperreal society surrounds the individual with a flood of fragmentary entertainment, information, and communication that provide more intense and absorbing experiences than mundane existence—and yet these are all simulacra, representations that have replaced reality. Eventually, these simulacra start to replace themselves, and we build our ideas around them instead of what they purport to represent.

We’re now closer to hyperreality than ever before—but again, AI memes are not the real problem here. I think creators like Mr. Beast are doing the exact same thing: making content for the sake of content, rather than something real. No, the platforms are the problem, because they want to trap us in a simulation of constant spectacle, and thus alter the way we construct our identities. Meaningless “content” is merely downstream of their business priorities.

To really fight back, then, we should always communicate with intention, avoiding the “content” trap even if it means going less “viral” (after all, that’s a manufactured priority). We should produce messages that carry a reality within them, not a representation of reality—for, as Baudrillard would warn us, the representations will eventually start replacing themselves.

If you liked this post, you might like my upcoming book Algospeak, which examines how algorithms are affecting our language. Please consider pre-ordering—it goes a long way to get booksellers interested + get on any best-seller lists :)

and thus the real villain is rampant commodification of everything again

"We should always communicate with intention,... We should produce messages that carry a reality within them..." Yes, we should, but how is this any different from saying corporations SHOULD prioritize the well-being of their consumers and communities over short-term profit? In other words, it's easy to say what people and entities should do, but what they will do is respond to the incentive structures within which they exist. Until those structures are changed, all the shoulds in the world won't add up to anything.