Has anyone else had a sneaking suspicion that YouTube videos are getting longer? Well, they are, and it all goes back to my number one lesson as a content creator: everything on social media platforms is designed to earn them as much money as possible.

The primary goal of YouTube and TikTok isn’t to entertain you—it’s to hold your attention for as long as possible so they can make ad revenue off you. Entertainment is a just a byproduct of that objective, which explains why there’s so much shitty clickbait and ragebait on the platforms: the content holds your attention, even if it’s not what actually entertains you the most.

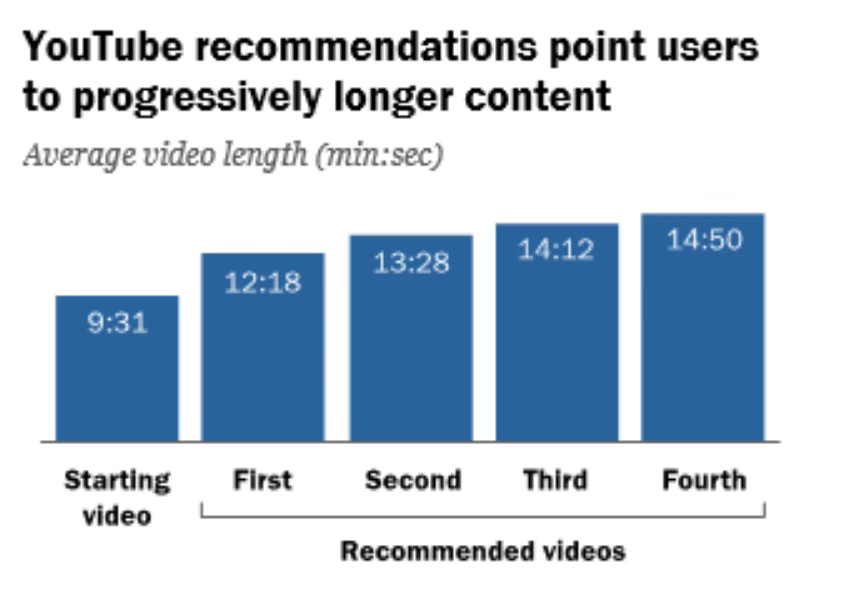

A similar phenomenon is happening with video length. Studies suggest that the average YouTube user prefers watching seven to ten minute videos,1 and yet YouTube will tend to push longer videos, which keep you on the platform longer and earn them more revenue through pre- and mid-roll advertisements.

This isn’t speculation. A 2018 Pew Research Center study ran 170,000 simulations on how YouTube recommends videos, and found that the algorithm quietly directs users toward longer and longer videos:2

Other analyses by the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose also suggest that, once platforms capture users within their content ecosystem, they increasingly disregard viewer preferences by subtly re-allocating their attention to more profitable parts of the platform.3

You can see this in how YouTube recommends that you resume watching long-form videos you clicked away from: they know that you’re likely to spend more time watching something you’ve already invested time in, and that it’ll make them lots of juicy mid-roll revenue.

Creators, in turn, are pressured to make ever-longer YouTube videos. Long-form content is not only more profitable for us, but also more likely to go viral because of how the algorithm works—so we respond by changing the format of our storytelling.4

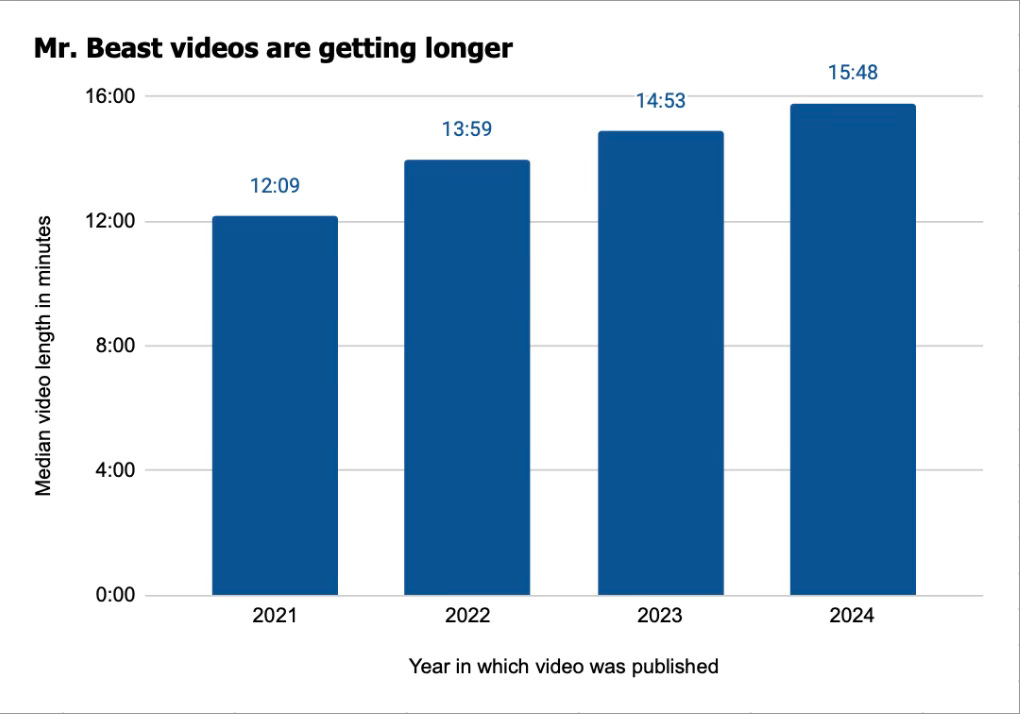

On a hunch, I decided to test this theory by looking at the 84 videos published by Mr. Beast from 2021 to 2024. Indeed, we see his median length increase every single year:

This isn’t an accident. Mr. Beast is very knowledgeable about changes to the algorithm, and is very intentional about responding to them. In his recently leaked employee manual, he obsessively writes about maximizing user retention and employing specific formats that work best for the algorithm. If his video lengths are increasing, it’s because he wants those video lengths longer.

All creators are trending in the same direction as they figure out what works, meaning that we’re collectively moving toward a future dominated by extended video essays instead of the ten-minute content viewers most want to see.

On the other end of the spectrum, of course, is short-form video. Social media companies can’t escape the reality that short vertical content is best at grabbing our attention, even if it doesn’t earn as much per video.

They have been able to push these longer to some degree—we’ve seen a shift away from Vine-length content on TikTok as the platform moved to only pay creators for minute-plus videos—but there’s ultimately a limit to what users will watch when the expectation is quick, addictive content.

In the case of YouTube, the Shorts feature in particular seems like a strategy to hook people onto the platform and then funnel them to longer content (which can conveniently be edited into minute-long Shorts that then link back to the original source). As a result, YouTube content is being stratified into either short- or long-form, with no real incentive to make the seven-to-ten minute mid-length videos most of us actually want to see.

As a linguist and content creator, I’m especially interested in the implications for online storytelling. As I weigh a move into horizontal YouTube videos, I’ll probably make my videos longer than I would have liked to, since I want them to perform better in the algorithm. This means that I’ll inevitably reshape my stories around the platform’s priorities, using different rhetorical choices and linguistic techniques than I otherwise might have. That’s a crazy thought.

Beautemps, Jacob, and André Bresges. "What comprises a successful educational science YouTube video? A five-thousand user survey on viewing behaviors and self-perceived importance of various variables controlled by content creators." Frontiers in Communication 5 (2021): 600595.

Smith, Aaron, Skye Toor, and Patrick Van Kessel. "Many turn to YouTube for children’s content, news, how-to lessons." Pew Research Center 7 (2018).

UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. 2024. “Algorithmic Attention Rents.” Omidyar Network. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/research/digital-economy-and-algorithmic-rents/algorithmic-attention-rents.

Ellis, Emma Grey. “Welcome to the Age of the Hour-Long YouTube Video.” Wired, Conde Nast, 12 Nov. 2018, www.wired.com/story/youtube-video-extra-long/.

Reminds me of how videographers had to change from horizontal to vertical filming for TikTok and the shift (if not sacrifice) that was required. Money, audience, and formatting restrictions have always shaped art, but it's disheartening these days to witness the true chokehold that a handful of companies has on the most democratized space for independent creators.

Good take as always. I really enjoy the underlying theme you currently have, basically about how we talk alters what we say, a topic that fascinates me to no end. Very happy I subscribed to this substack