the engagement treadmill: how algorithms perpetuate new words

and how that's connected to the brainrot aesthetic

Viral videos are like the Kardashians: at a certain point, they only become popular because they’re already popular.

If you look at any of the top-viewed TikTok videos, they’re no more compelling than any other moderately viral TikTok. Instead, people are watching those videos simply because other people watched them first.

We might want to be caught up on a shared reference. We might see a high like count that piques our interest. We might just be fascinated with what others find fascinating.

This kind of herding behavior is called an information cascade, and it also explains why other videos do poorly. If you come across a video with a low view count, you might assume that it has low social value to you, or that it’s previously proven to be a poor-quality video. Either way, you scroll away.

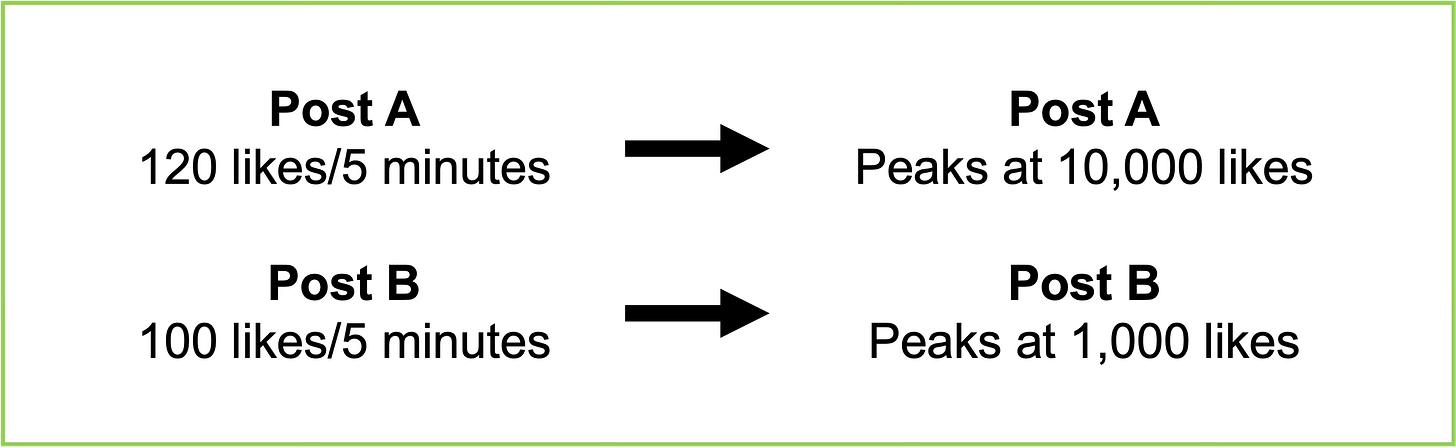

Social media algorithms not only mimic but amplify this natural human behavior by rewarding videos with better engagement. If Post A receives 20% more likes than post B in the first few minutes, the algorithm isn’t going to push Post A to 20% more people—it’ll push it to 900% more people.1 As a result, Post A is going to cascade in views, vastly outperforming Post B even though it was only 20% catchier.2

Algorithms don’t just do this with individual posts. They do this with entire trends, by incorporating every piece of information they can gather, like popular audios or metadata. This is why you keep seeing videos with the same sounds and hashtags: once they start trending, the algorithm keeps pushing them to optimize for popularity.

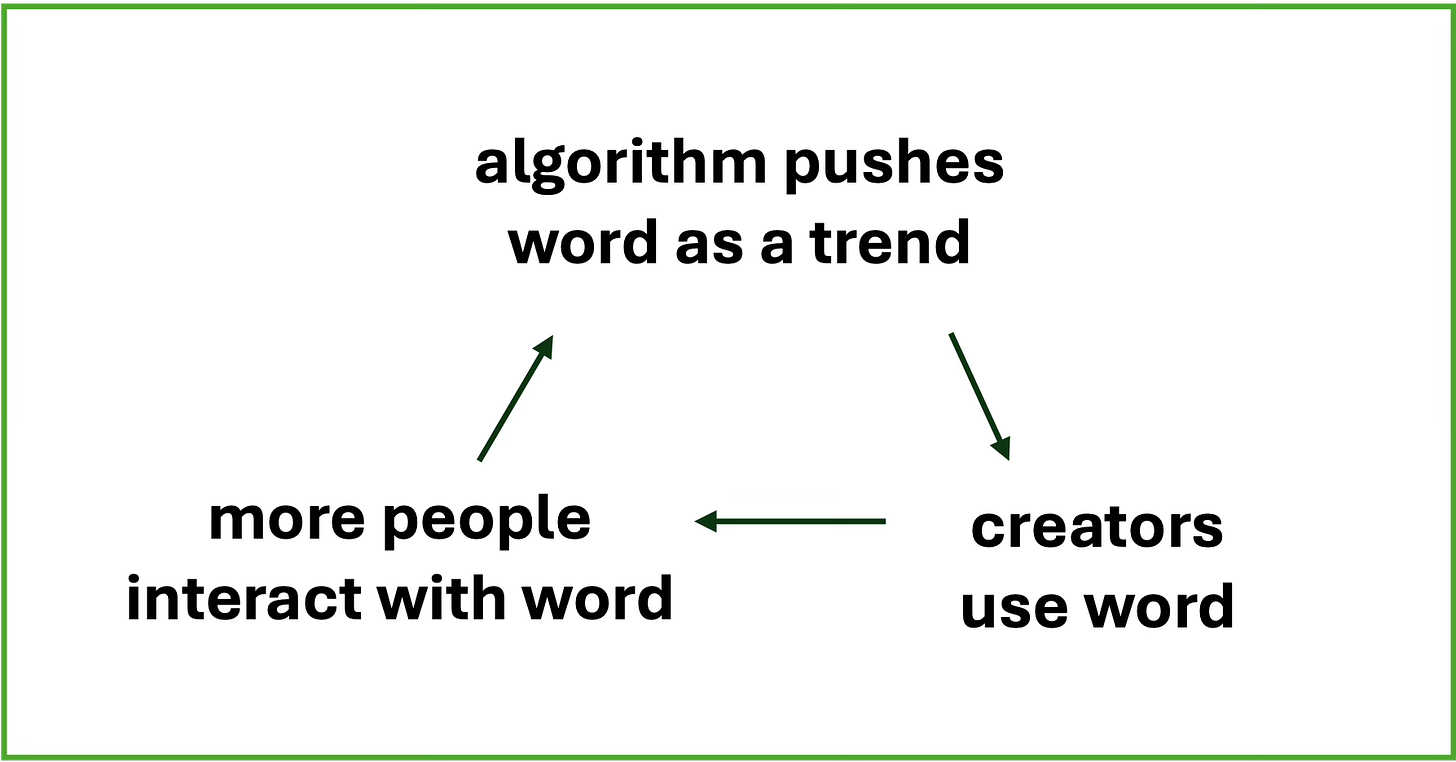

Content creators directly accelerate this positive feedback loop by using trending metadata in our videos. Our job is to go viral, so we’ll use our knowledge of the algorithm to do just that.

This includes words, which are interchangeable with metadata. If the word “demure” is trending, more creators will make “demure” videos because the algorithm is more likely to push it as part of the demure trend. On an individual level, people are also fascinated with the word because they know it’s popular, which is exciting to them. Then the algorithm registers that as increased interest in #demure and cascades the term into a large-scale phenomenon. I call this the Engagement Treadmill:

The pattern is clear. Virality begets more virality—and this explains a lot of new etymological patterns. Creators and platforms deliberately use emerging language to capture our attention, inadvertently helping that language spread faster than it otherwise would have. Eventually, the meme might die, but its impact remains: I now hear my ten-year-old cousin use the word “demure” without any knowledge of its meaning.

On a certain level, we can feel our culture pooling downstream from the algorithm, and our resulting fatigue informs our collective sense of humor.

In a recent substack post, for example, I wrote that a defining feature of “brainrot words” is that they get “repeated as memes to the point of nonsensicality.” I stopped short of explaining why they get repeated, however, and that’s because I was saving my explanation for this post: the brainrot aesthetic emerged as a direct result of the engagement treadmill.

Each “brainrot word” like rizz, skibidi, and gyat happened because it blew up as a meme, got overused by “cringe creators” trying to capitalize on the meme, and became so algorithmically saturated that the word itself became a reference to the greater canon of “overused internet language.”

The implication of brainrot has always been that it’s harmfully tied to social media trends that “rot our brains,” and yet there’s nothing inherently bad about brainrot words themselves. Instead, the terms become memes because they scare us. They serve as reminders that our trends are predetermined by social media virality, and comedy is our only coping mechanism.

Narayanan, Arvind. 9 March 2023. “Understanding Social Media Recommendation Algorithms.” Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University.

Note that Post A doesn’t have to be intrinsically better— only better at catching your attention. This is why clickbait and ragebait videos are so good at going viral: they get engagement, which is rewarded by the algorithm.

i wonder if SubStack also has a similar recommendation algorithm. anyhow, commenting here to boost the algorithm 😈😈🥶

It’s like we’re stuck in this infinite game where creators and platforms keep optimizing each other.