Museums have kind of been freaking me out recently.

It’s deeply frustrating that I’ll never be able to interact with an artwork as it was actually intended. Instead, I’m forced to interpret it through the social context of a contemporary museum, which changes the way I look at it.

Consider El Greco’s Opening of the Fifth Seal, originally made for a side-altar in a church in Toledo, but now displayed on a blank gray wall in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

El Greco never meant for his painting to be viewed this way. New York didn’t even exist during his lifetime, nor did an “art museum” in the modern sense. Rather, the piece had a devotional purpose, as a conduit between worshipper and God. You would look at it as a means for religious connection, not as an end.

Once the Opening of the Fifth Seal was put up in a museum, however, we began treating it less as a point of faith and more as an object of aesthetic contemplation. The museum came with a completely different premise, so we also began viewing the painting differently.

In his seminal work Ways of Seeing, the English art critic John Berger argues that this happened so that the ruling class could exercise power over art. By setting aside the act of looking in a new sociocultural context, the elites not only physically isolated artworks but imbued them with their authority. Now the only way to “properly interpret” El Greco is through the language of the upper-class art world.

Of course, that defeats the original purpose. When I look at The Opening of the Fifth Seal today, the ritual is lost. Going to the museum, admittedly, is another type of ritual, but a flatter one that loses some of the meaning of the original: the signs and symbols of worship are compressed into a more secular encounter, making it harder to connect with God the same way.

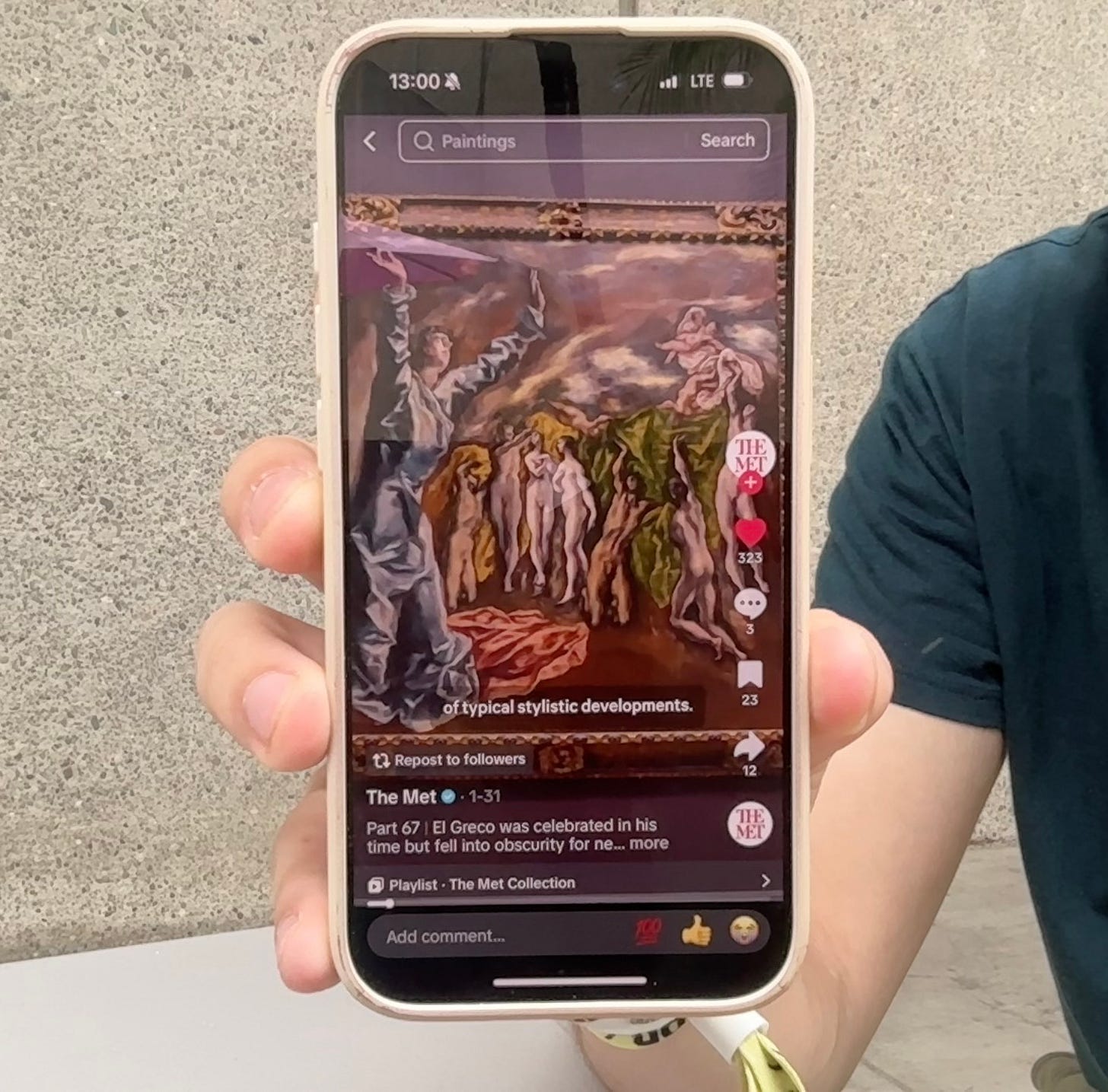

I’ve previously analyzed how scrolling on social media is essentially a ritual, in that it’s a segmented portion of reality we use to contextualize our existence. But now I can’t help but think about all the previous rituals that were compressed to make this one happen. What if TikTok is the modern museum—an institution changing our appraisal of aesthetic experiences?

My first lament is for the movie. In the past, the act of watching video was more sacralized. We would go to the theater, get popcorn, wait through the ads, and get excited when the lights dimmed. Even at home, the act of viewing films felt more special than the way we scroll today. There were more symbols to interpret, more meanings to construct, simply because it felt like a more discrete part of our conscious experience.

Now I’m thinking of music. On the modern social media platform, the experience of watching video and listening to songs is all rolled into one. But why does it still feel more magical to pull a record out of its sleeve, place the needle, and listen to the gritty music emerge from a record player? It was more of a ritual, there was more meaning to interpret, and at the end of the day humans operate on meaning.

Even a meme or trend would feel more special when you heard it from a friend, rather than a viral video. There’s something to an organic-feeling, word-of-mouth phenomenon that just carries more authenticity. Again, this is compressed through the algorithmic oversaturation of memes, the same way you might connect less to a painting when it’s surrounded by hundreds of other paintings.

Maybe social media makes us feel worse about ourselves because it removes all these little meaningful actions from our lives—rolling them all into a single, mass-produced experience. Ironically, with more things happening at once, there are fewer things to interpret; ritual demands time and space, but we consume an endless stream of space without time. We end up as detached spectators, looking at paintings in museums rather than churches.

Much like museums, algorithms also affect the distribution of power in society. By removing media from its original context, the platforms are able to exercise more control over information. Now we have to view communication through their lens—reconstructing meaning with less agency for ourselves.

There’s really no way to fight this. You can’t pretend the algorithms aren’t there. Even off of social media, their audiovisual logic affects the way we see and relate to each other. But you can be aware of what they’re doing, reclaiming micro-rituals where you can and harnessing the platform’s symbols for good. In the words of John Berger:

“the art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost. In its place there is a language of images. What matters now is who uses that language for what purpose.”

If you liked this post, please consider pre-ordering my book Algospeak, which comes out in less than a month! Pre-ordering is the best possible way to support authors :)

Also! Book tour dates:

NEW YORK, July 14 - 7 pm conversation with Depths of Wikipedia founder Annie Rauwerda in the Strand Bookstore Rare Book Room (ticketed here)

BOSTON, July 16 - 7 pm Harvard Book Store (listing here)

MENLO PARK, July 18 - 6 pm Kepler’s Books (ticketed here)

WASHINGTON, D.C., July 25 - 7 pm conversation with Filterworld author Kyle Chayka at the Politics & Prose Wharf Bookstore (listing here)

I know this post is not about me and is making great thoughtful points, I just couldn’t help get a little frustrated by the cynical take on museums. To be recognized as a nonprofit museum the organization must prove they’re a public benefit and that they're educational. Plenty offer an experience beyond just looking at art hung up on a plain wall. I mean the wall shouldn’t be attention grabbing in the first place if you’re trying to display art. Often the people working in them provide more cultural context than I would have if I had just passed it on the street. The opportunity to even see them is often only possible because of the preservation efforts of that organization. Okay I’m a little impassioned because I work for a tiny nonprofit museum and I have so much respect for everyone here, many just volunteers who want to make their community a better place. Your inability to experience the piece as it was intended for its time is a part of being human and experiencing the remnants of the things that came before us… even if it was up on a wall for you to pass by

I love this line, near the end.

“Ironically, with more things happening at once, there are fewer things to interpret; ritual demands time and space, but we consume an endless stream of space without time.”

I think you’re positively DEAD ON. We have music and film at our fingertips, but hold it cheaply because of its immediacy. We have art, but cordoned off in institutions of art that gate-keep the viewing experience. Language, but not world-of-mouth, but screen-shared. Stimulus, Stimulus, Stimulus, and no space for a response. The symbols start failing to deeply signify any longer due to over-saturation.

Great read.