neural networks are changing our vibes

Last week, I published two op-eds that initially seem unrelated but actually aren’t.

The first, for the New York Times, was about how Donald Trump is influencing the English language. From phrases like “many such cases” and “many people are saying this” to “sad!” as an interjection, Trumpisms are seeping into our regular vocabulary—first through ironic usage, then through genuine application.

The other op-ed, for the Washington Post, was about how we’re all starting to talk more like ChatGPT. We’ve known for a while that LLMs overrepresent certain words like “delve”; now we have proof that people are saying “delve” more in spontaneous, spoken conversations.

Both of these examples point to something I’ve long felt lacking in academic linguistics: the importance of our “vibes,” or ambient evaluations of a situation. People aren’t saying “sad!” or “delve” out of a deliberate decision to adopt and replicate those words. Instead, we see them represented, subconsciously internalize them into our “mental lexicon”—our mind’s “dictionary” of possible utterances—and then draw on that lexicon to repeat the words in the future.

When our speech changes, that’s because of a changing “vibe” of how we can articulate ourselves in a given situation. But this is determined by the language we see as available to us, meaning that our vibes are influenced by the chokepoints of linguistic dissemination.

The reason we’re talking more like Trump and ChatGPT is because our language is being bottlenecked through algorithms and large language models, which do not represent words as they naturally appear: they instead give us flattened simulacra of language. Everything that passes through the algorithm has to generate engagement; everything that passes through LLMs is similarly compressed through biased training data and reinforcement learning. As we interact with these flat versions of language, we circularly begin to incorporate them into our evaluations of how we can speak normally.

The philosophers Deleuze and Guattari would note that these linguistic representations actually perform as mots d’ordre, or “order-words”: utterances that implicitly structure reality and create norms for us to replicate. In the same way that a teacher produces a “grammatically correct” version of English for their students to learn, these new technologies are producing their own version of English, which we’re also replicating.

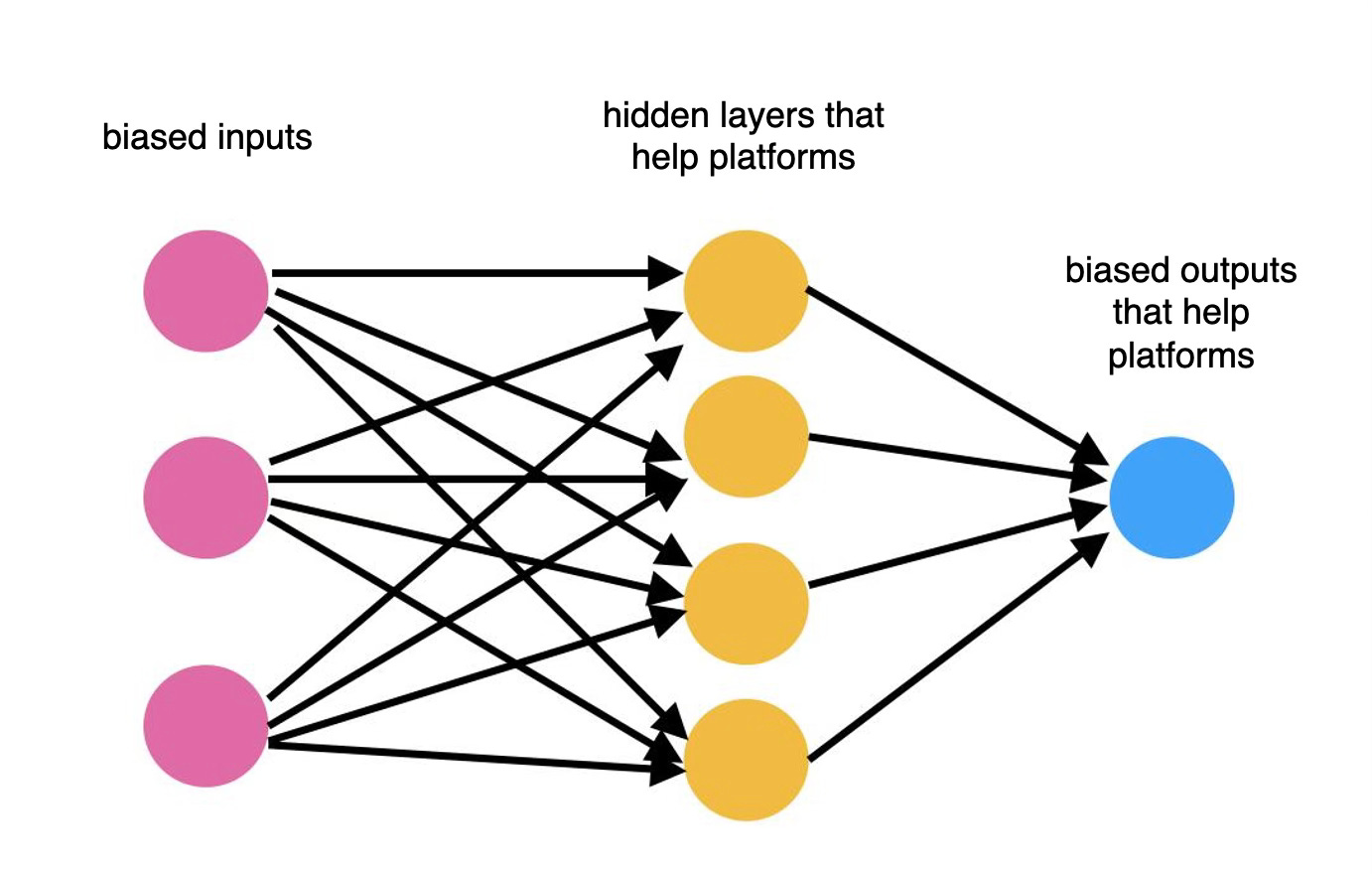

This is inevitable. ChatGPT and recommendation algorithms are both based on neural networks, a form of artificial intelligence that learns from its inputs to produce new outputs. But those outputs are always going to depend on the inputs, which will always differ from reality, as a map from its territory. So any interaction we have with neural network-based media is going to change our vibes.

But what happens when those vibes impose power? We know that algorithms only present content that aligns with platform priorities, and that LLMs (looking at you, Grok) can clearly be manipulated to promote certain ideologies. Mots d’ordre definitionally impose order—and in this case, that order benefits Big Tech.

Deleuze and Guattari do identify a counterpart to the order-word: the mot de passe, or “pass-word.” In contrast to a performative production of cultural hegemony, the pass-word opens up a new territory altogether, allowing our speech and ideas to escape in a new direction.

I believe that internet memes are those mots de passe. If you look at the modern state of comedy, our jokes are in constant flux, reacting to current technology. References to “clankers” and absurd AI-generated images challenge the status quo of how generative intelligence should be used; “brainrot” reflexively responds to algorithmic oversaturation. These memes create resistance where you normally expect order—giving us a chance to reclaim our vibes.

love the Deleuze/Guattari application -- so fascinating the way our language is constantly bending with power and then bouncing back as people use it. They can never fully centralize, control, etc... we just gotta hope that one of these mots de passe ends up being a spark that catches and helps change the order into something better, maybe

They can't sell us a better joke than the inside joke we have with ourselves.