At some point in the last century, we collectively began looking at more representations of stars than stars themselves.

The representations have always been there—as early as 40,000 years ago, Paleolithic people were thought to leave sophisticated star charts on cave walls,1 and since then we’ve used them in our flags, emblems, and home decor alike—but most of these depictions were made at a time when the full Milky Way was completely visible to the average observer. Since the Industrial Revolution, however, more and more stars have been made invisible through light pollution, changing our relationship with “stars” as a concept.

Today, I see dozens of star emojis every day on the internet, but only a handful of real stars when I remember to look. 🤩⭐️🌟💫

This is insane when you consider how important stars were to people in the past. Apart from navigation and timekeeping, the night sky was how they constructed their worldviews. An ancient Roman could look up, without any light pollution, and immediately get lost in the dizzying expanse of the full cosmos. This soul-shattering feeling sprung forth entire mythologies and religions revolving around those stars.

You can sort of see the vestiges of this in our language. The words desire and consider both come from the Latin word sidus, meaning “star,” because our very emotions were thought to come from the stars.

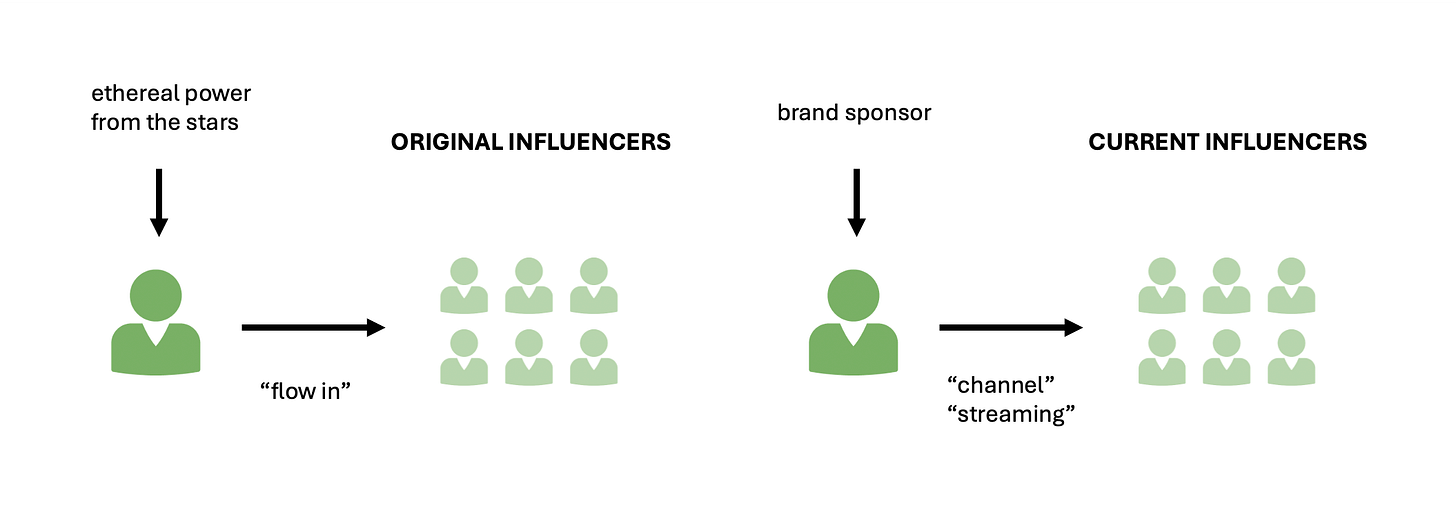

The word influence is another fascinating example, from the Latin words for “flow in.” When the verb was first borrowed into English in the 14th century, it was an astrological term referring to an “ethereal power streaming from the stars to act upon a person’s character and destiny.” When someone influenced someone else, they channeled this cosmic power to sway that person’s destiny as well.

Today, the word influencer is still around, but detached from the stars. It still has a connotation of “flowing,” which is why influencers have YouTube channels or Twitch streams (conduits for power), but the thing that’s flowing is usually commercial: a brand sponsorship or advertisement.

The words “desire” and “consider” were similarly secularized, as were our depictions and language around stars. When we praise someone by calling them a “star,” we don’t think about how that phrase was popularized by Chaucer, who borrowed it from Ovid, who wrote in his Metamorphoses about humans literally being transformed into constellations.2

Light pollution alone doesn’t explain this loss. In his book Landscape and Images, the American historian John Stilgoe argues that, because of technology, our perception of landscape has changed not just in what we see, but in how we see. Even if you look at the full night sky today, you wouldn’t draw the same meaning as an Ancient Roman, because we’ve lost the interpretive framework of seeing it as divine. More of our experience is also mediated—looking down at our phones instead of looking up at the stars—which displaces our sensations, making it harder to see normal things with the same level of significance.

At the same time, why are there so many stars on the internet and why do we still use all these words? Language has always been a palimpsest of things that mattered to people in the past, and it’s beautiful that we still find meaning in these echoes. New meanings, sure, but the words still matter to us in their own way. Hopefully they can also serve as additional reminders to look up when we can.

If you liked this post, there are only two weeks left to pre-order my book Algospeak if you also want to get a free poster! Pre-orders are the best way to support me as an author <3

Also! Here are my book tour dates if you want to meet me and get your copy signed:

NEW YORK, July 14 - 7 pm conversation with Depths of Wikipedia founder Annie Rauwerda in the Strand Bookstore Rare Book Room (ticketed here)

BOSTON, July 16 - 7 pm Harvard Book Store (listing here)

MENLO PARK, July 18 - 6 pm Kepler’s Books (ticketed here)

WASHINGTON, D.C., July 25 - 7 pm conversation with Filterworld author Kyle Chayka at the Politics & Prose Wharf Bookstore (listing here)

Sweatman, Martin B., and Alistair Coombs. "Decoding European Palaeolithic Art: Extremely Ancient Knowledge of Precession of the Equinoxes," 2018. arXiv:1806.00046

Garber, Megan. “Why Are They ‘Stars?’” The Atlantic, February 24, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/02/why-are-celebrities-known-as-stars/517674/

i love everything u write, I've always loved books and writing but the you made tje linguistics of everything so interested, I'm buying the book as soon as i can afford to xoxo

Fascinating and much needed. I’m glad more people are talking about light pollution and the effect a lack of exposure to seeing the stars is having on us. Some people have even mistaken stars and planets for drones and UFOs in recent years! Our ancestors would be laughing at us…

Not only this but we see more stars online in the form of photos from space, like Hubble and JWST, the irony being that the more advanced and detailed our space images get, the less we see of them with the naked eye.

There are some books about this, I have yet to read them but they go into this a lot, as in, the cultural side of stargazing and how it’s decreased because of light pollution: The Human Cosmos by Jo Marchant and Starborn by Roberto Trotta.

And I’m also thinking about the recent rise in astrology. How it’s become so popular in the last decades or so and people are taking it seriously, not just the pop ‘oh what’s your sign?’ stuff but some really go deep into the classical forms of astrology. Whatever one thinks of it, as a bit of fun, or as pseudoscience, or as a spiritual practice which people find helps them in a way, perhaps it shows that people still feel a pull deep inside, a desire (ha!) to find meaning in the stars… (regardless of what one might think of astrology and its validity, I’m mentioning it as a cultural phenomenon purely here)