If you’ve spent any time on social media in the past three months, you’ve probably come across “hopelesscore” videos in your recommended feed.

The meme genre—in which depressive language is presented motivationally to mock the earlier “hopecore” aesthetic—first started taking off on TikTok in November, and the first few memes were really funny.

Phrases like “I will never quit drinking” overlaid onto a waterfall and “fuck you” on top of a beautiful sunset seemingly harnessed a sense of collective defeatism by turning it into absurd humor, romanticizing failure and depression in a way that clearly spoke to millions.

As a reaction against previous “core” aesthetics, hopelesscore also fundamentally did the same thing as “corecore” in 2022: it wryly poked fun at the oversaturation of social media aesthetics. This was almost definitely part of the appeal. People liked that it subverted the never-ending pipeline of online “content” with something raw and genuine.

At least that’s how it started.

As my feed has gotten more clogged with “hopelesscore” videos, I’ve instead come to notice a shift in the style.

Now accounts like “chainedcores” and “hopelessed.core” are churning out multiple hopelesscore videos a day, sacrificing the quality of the videos to make as many of them as possible. Rather than getting at something real, these mass-produced videos are simply another engine for farming content. Any mildly funny audio can get recycled into a hopelesscore edit, just as it can be overlaid onto Subway Surfers or duetted with a soap-cutting video.

In short, hopelesscore has become “content” like any other online aesthetic, resigned to being farmed by TikTok spam accounts. The actual message, meanwhile, is losing its meaning.

This is a pattern I’ve seen play out again and again online. A reactionary force on the internet tries to send us a message, people engage with it, and then it immediately gets commercialized. This is exactly why “corecore” died out as well: the trend cycle collapsed in on itself after too many creators tried to milk it for a quick buck. I’m also reminded of how Luigi Mangione instantly got turned into an aesthetic, or how the “brainrot” meme genre is locked in a constant spiral of escalating “content.”

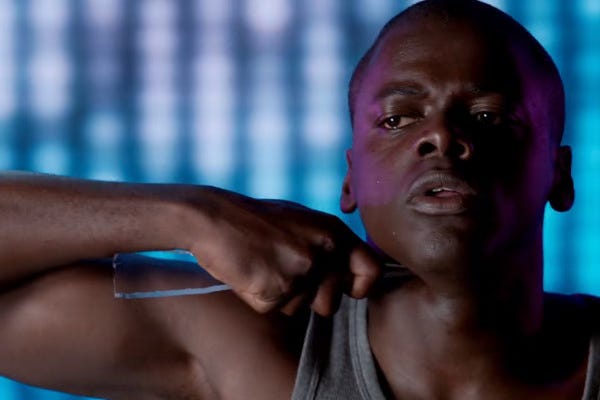

I can’t help but analogize this to the “Fifteen Million Merits” episode of Black Mirror. In it, the character Bing tricks his way onto a talent show and uses the platform to criticize his dystopian, hyper-commodified reality. His passionate rant impresses producers, who give him his own show. He then continuous to criticize the system from his luxury apartment, but it’s clear that the idea has been corrupted.

When you look at the first hopelesscore or corecore videos, the initial Luigi memes, or the idea behind brainrot, they’re all Bing holding a shard of glass up to his throat screaming about a broken society. This is why they spoke to us: they satirized the inescapable problems of modern existence.

But because those problems are inescapable, each aesthetic eventually ended up being subsumed by them. In the end, our message got packaged to us from within the system it was meant to react against.

As a creator, I constantly feel this. I criticize the algorithm, but depend on the algorithm for my career. I see words emerge in response to an increasingly enshittified social media landscape, but those words require that landscape to exist. So, from my luxury apartment, let me warn you: don’t forget how the medium affects the message.

This reminds me of Mark Fisher's argument in Capitalist Realism, namely the way capitalism absorbs and commodifies critiques of itself.

"enshittified" omg brilliant