algorithms are killing coincidences. what does that mean for language?

Let’s start with the basics: humans do not think like machines do.

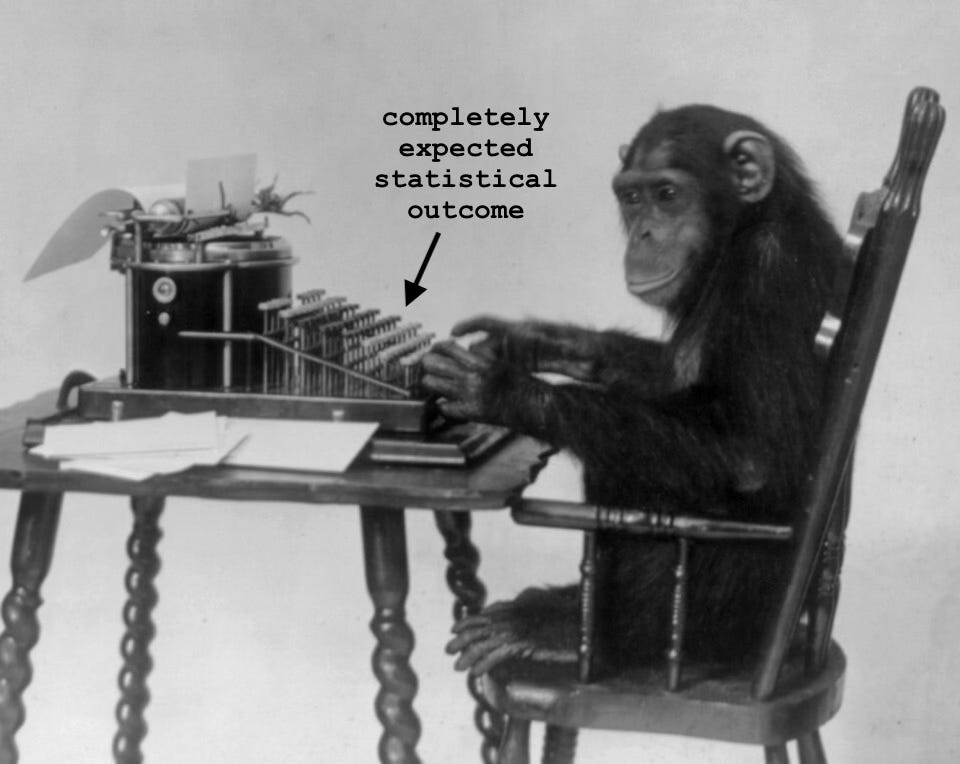

An algorithm models the world through statistical relationships, and attempts to control it through prediction. Any “coincidences” in the pattern are ignored as expected mathematical anomalies.

A human does not have the same understanding of probability. When we see a “coincidence,” our first instinct is not to write it off as an outlier; it’s to tell a story.

If I meet someone in a bar and find out we’re both from Albany, NY, that wouldn’t be interesting to a machine. It’s akin to the Birthday Paradox: a probable event every once in a while, easily explainable through statistics.

To me, though, the Albany fact is a shared experience bringing me closer to the other person. I construct a narrative in my head that we are similar to each other, and use that as a launch point for our conversation. As we talk, we discover that we had a mutual friend in high school. Once again, this is statistically probable, but it nevertheless strengthens our interpersonal bond.

The coincidence becomes a story. In fact, I would say that coincidences are the defining feature of stories, which exist to connect people or events in our minds.

It’s literally in the word: the concurrence of incidents. If I’m telling you about my flight from Bangkok to Taipei, I’m bridging the incident of me being in Bangkok with the incident of me being in Taipei. Same with any other story: it creates a mental continuity between arbitrary events—one that helps us make sense of the world. A coincidence, therefore, is an epistemic tool forming the basis of human knowledge.

But what happens when our coincidences are engineered out of existence?

As I wrote in my previous substack post, social media algorithms are fundamentally designed to eliminate coincidences. They optimize for predictability, since more predictable consumers are more profitable. They want us to stay indoors and isolated so that they can mediate more of our interactions. They neatly categorize us into separate filter bubbles, making it easier to impose their ordered version of reality. All of these priorities remove randomness from our lives, putting the algorithm at odds with our most important story-telling device. That’s going to change how we think and communicate.

The most immediate concern to me is loss of creativity. There is a growing body of literature suggesting that perception of coincidence correlates with creativity. If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense: seeing coincidences means finding connections or patterns that are usually hidden from view. That helps us overcome mental blocks, think outside the box, and come up with new ideas.

Consider the importance of randomness in academia. In my own research, I’ve occasionally come across weird, lesser-known papers that helped me craft more unique arguments than if I had just used more widely known sources. I only found those lesser-known papers through coincidence: stumbling across a book in a library that happened to connect to my work.

But what happens when the Google Scholar algorithm pushes more-cited papers to the top, and then ChatGPT encodes that into its recommendations? We abstract several degrees from randomness and get more homogenized research as a result. Now I might come up with a less original thesis—and that’s not even getting into the fact that LLMs are being trained on their own output, recursively giving me an even less diverse list of sources to choose from.

“Creativity” means weaving together random data points in a meaningful way. If everyone is getting the same data points, though, it follows that we’re going to lose some creativity. We’ll have fewer new coincidences to notice, which means fewer “eureka moments” of spontaneous lateral thinking.

Fewer coincidences also means fewer opportunities for human connection. If we’re all in our separate echo chambers, not noticing our funny little similarities, it becomes easier for us to feel polarized. There’s no mechanism for shared story-making, like connecting with my new friend in the pub.

Why does it feel so much better to recount the story of a meet-cute than a Hinge match? I don’t think dating apps are that stigmatized anymore. Rather, saying “we met on Hinge” is a conversation ender, while explaining how you bumped into each other on the street prompts further conversation. Meeting someone through a neatly ordered, algorithmic pairing isn’t as good for generating a story, and humans thrive on stories.

Coincidences are linguistic adhesives that we use to piece together reality, and then to bond with one another. That process relies on subjective meaning-making, not the statistical logic of machine learning.

In fact, over-engineering is actively detrimental to the storytelling process. A coincidence loses its rhetorical power if it feels too planned. It’s not a funny story if my new Albany friend had known who I was in advance, stalked me to the pub, and declared our shared hometown. Rather, the coincidence must feel random, beyond imagination—only then does it become a story.

Algorithms are like stalkers: they know everything about you, and try to over-engineer reality to fit their predictions. There’s nothing coincidental about that—and so we ultimately interpret less meaning. If I get two videos about the same thing on my For You Page, for example, I don’t see it as serendipitous because I know it’s targeted. So I don’t make a story. I get confined to the disjointed yet predictable reality of the algorithm, a narrative prisoner of efficiency.

If you liked this post, please consider pre-ordering my book Algospeak, which examines how algorithms are affecting our language!!! Pre-orders are the best way to support authors <3

Basically we need to bring back 2014 tumblr and BEING RANDOM XD

Humans thriving on stories is so real. We are nothing without the narrations of all our experiences.