against content

I’ve always felt that it’s very strange to have “followers” on social media.

Before the internet, a “follower” was either your stalker or a member of your cult. Since then, we’ve somehow normalized the phrase and it’s now very desirable to have a high “follower count.”

Even more strangely, these followers are treated as interchangeable with one another. When Instagram tells me that I have “1.6 million followers,” that includes spam accounts, duplicates, and many actual people—all numerically valued the same, even though they are all so complex in their own ways. To talk about my “follower count” is to de-individualize those people and reduce them to commodities.

This is known as the reification fallacy: the act of treating an abstraction as the real thing. The user interface and language of social media incentivizes reification, because that’s what the platforms want.

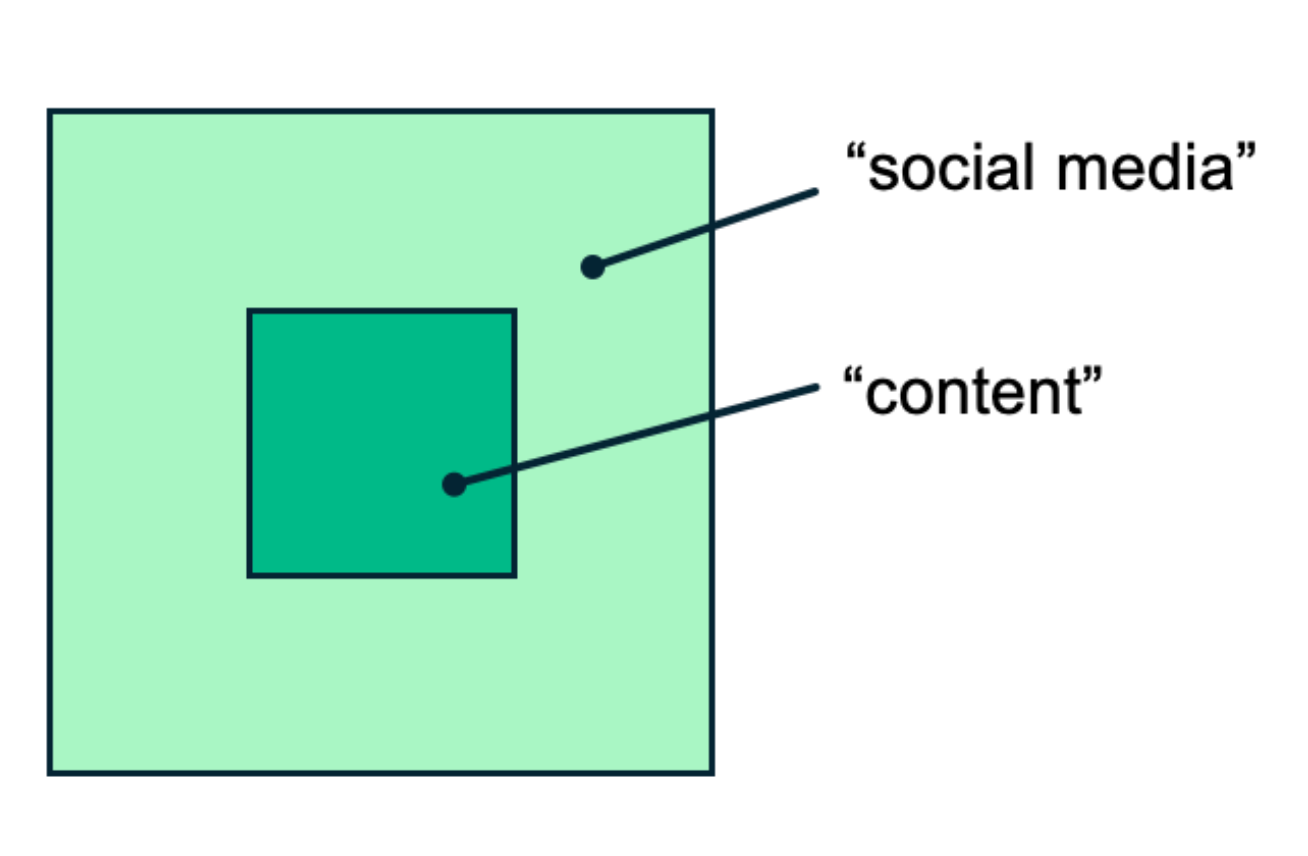

Look at how we call videos “content,” implying that they’re somehow “contained” like the “contents” of a box or drawer. The metaphor here is that videos are held in the “medium” of social media.

As soon as you accept that videos are content, now they become something that you can scale up and mass-produce, which is great for social media companies that need to fill up space between ads:

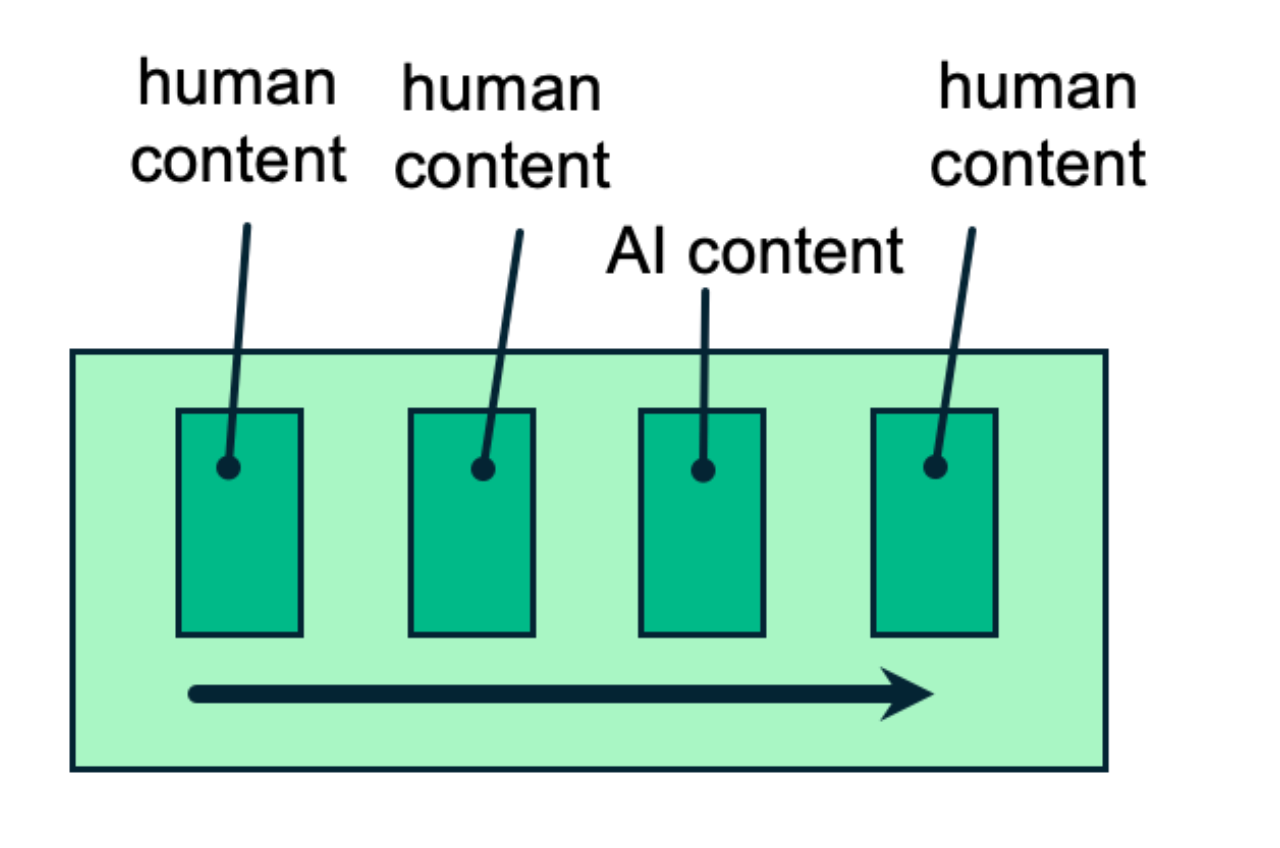

However, because this is a reification, it doesn’t actually matter what’s inside the “content” itself. Just as my “follower count” contains a mix of real people and bot accounts, so too can “content” contain a mix of human- and AI-generated videos:

Logically, slop is completely okay—if you accept that videos are the “content” instead of actual ideas meant to connect humans to other humans.

This difference is what the media theorist James Carey calls the ritual view versus transmission view of communication. In the ritual view, communication is an act of sharing or fellowship between people. This is reflected in how the word “communication” itself shares a root with “community” and “commonality”: the original reason for why we would talk to each other was to maintain oral tradition and create a shared identity.

With technology, however, we start to confuse our own intentions. Carey demonstrates how the telegraph reframed communication through a “transmission view” where we started to value the information transmitted above all else. People would shorten their messages to save money, leaving behind actual ritual to communicate efficiently across long distances.

Since then, we’ve increasingly been losing touch with the ritual view. The twentieth and now twenty-first centuries have been all about communicating faster and better to a larger audience—sacrificing connection for transmission. You can see this reflected on social media platforms today; the only thing that matters is getting the maximum number of eyeballs on your “content” so you can build a higher “follower count.”

Unless, of course, we challenge that metaphor, and recognize that we’re actually communicating so we can have something in common.

Media updates:

The New York Times Book Review wrote about Algospeak in their most recent edition; read their review here

Podcast appearances with Taylor Lorenz, Galen Druke, and Morgan Sung

I talked to NPR, NBC, and Rolling Stone about the word “clanker” and to the NYT about the word “hypergamy”

A good case study in how the words we use for things both reflect and alter how we think about them. I see the rebranding of “creators” as “influencers” (as part of an effort by social media platforms to market themselves to advertisers) in a similar light. When online creators started referring to themselves as influencers that speaks to how they increasingly shamelessly view their job as being vehicles for selling products to their audience rather than, you know, creativity.

“sacrificing connection for transmission. “